Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Knowledge of Reference and Pragmatics

Reference

Steve’s 13:11 utterance of ‘Earth’ refers to Earth

Knowledge of Reference : what is meant?

1. Steve knows Earth (either by acquiantance or description).

2. Steve knows that his 13:11 utterance of ‘Earth’ refers to Earth.

3. There is a state of Steve’s mind in virtue of which his 13:11 utterance of ‘Earth’ refers to Earth.

Q1 What, if anything, is that state of mind?

Q2 Why think there any such thing as this state of mind?

At bottom, communication with words is a matter of following rules.

This can be done without any insight into why the rules are as they are.

Therefore mental states of communicators in virtue of which their utterances refer are unnecessary for characterising reference.

cf Putnam 1978

‘I’ve had a great evening. This wasn’t it.’

MS, the meaning of the sentence;

PE, the proposition expressed; and

PM, the proposition meant.

Neale, 1990 p. 75

I have had breakfast.

I have had a kidney removed.

I have had fermented fish for breakfast.

I have had a great evening.

Among utterances of these sentences,

there can be is variation in the PM

although Compositionality does not permit corresponding variation in MS.

Given that MS is a function from contexts of utterance to propositions,

the values of this function will not typically be a PM.

Terminology: Call the value of MS in a given context of utterance the ‘proposition expressed (PE)’.

MS, the meaning of the sentence;

PE, the proposition expressed; and

PM, the proposition meant.

Neale, 1990 p. 75

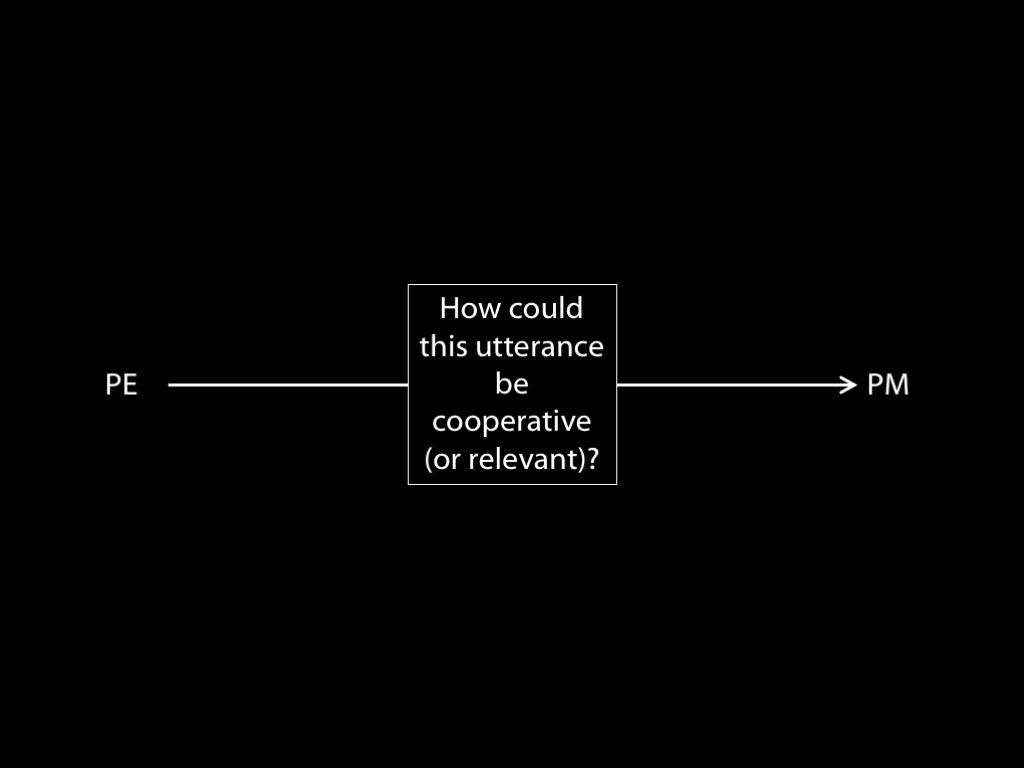

How do you get from PE to PM?

reasoning about cooperation (Grice)

searching for relevance (Sperber & Wilson)

At bottom, communication with words is a matter of following rules.

This can be done without any insight into why the rules are as they are.

Therefore mental states of communicators in virtue of which their utterances refer are unnecessary for characterising reference.

cf Putnam 1978

Two Arguments

1. Communication with words involves successful communication of a PM.

2. Which PMs an utterance communicates depends on context in arbitrarily complex, uncodifiable ways.

Therefore,

3. communication with words cannot be entirely a mechanical, script-following, rule-bound

activity.

1. Arriving at a PM depends on taking the PE and searching for cooperation or relevance.

Therefore,

2. communication requires representing PEs, which requires knowledge of reference.

Reference

Steve’s 13:11 utterance of ‘Earth’ refers to Earth

Knowledge of Reference : what is meant?

1. Steve knows Earth (either by acquiantance or description).

3. There is a state of Steve’s mind in virtue of which his 13:11 utterance of ‘Earth’ refers to Earth.

Q1 What, if anything, is that state of mind?

Q2 Why think there any such thing as this state of mind?

When the utterance of a word refers to a thing,

must the utterer have knowledge of reference?

What is the relation between

an utterance of a word (or phrase)

and a thing

when the utterance refers to the thing?

It is a psychological relation.