Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Knowledge of Reference (Part 2)

‘There is a common-sense picture of the relation between knowledge of reference and pattern of use.

... you use the word the way you do because you know what it stands for’

Campbell, 2002 p. 4

Reference

Steve’s 13:11 utterance of ‘Earth’ refers to Earth

Knowledge of Reference : what is meant?

1. Steve knows Earth (either by acquiantance or description).

2. Steve knows that his 13:11 utterance of ‘Earth’ refers to Earth.

3. There is a state of Steve’s mind in virtue of which his 13:11 utterance of ‘Earth’ refers to Earth.

Q1 What, if anything, is that state of mind?

Q2 Why think there any such thing as this state of mind?

‘There is a common-sense picture of the relation between knowledge of reference and pattern of use.

... you use the word the way you do because you know what it stands for’

Campbell, 2002 p. 4

When the utterance of a word refers to a thing,

must the utterer have knowledge of reference?

Characterising communication by language should be done

from the communicators’ persectives.

?

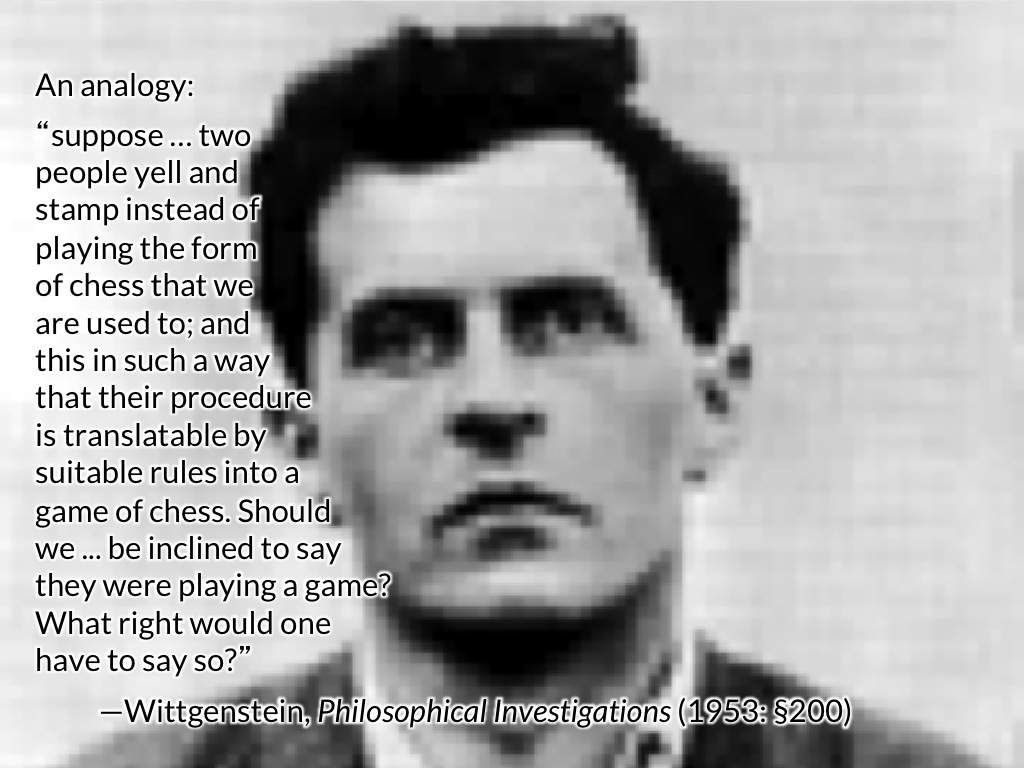

‘to attribute to a speaker no more than knowledge of how to play … interlocking language games is to make him a participant in an activity he cannot survey (‘cannot see what is going on’)’

Dummett, 1979 p. 224

When the utterance of a word refers to a thing,

must the utterer have knowledge of reference?

‘On the model just sketched, one can use one’s language [...] without any [...] notion of truth [or reference].

The instructions the mind follows, in this model, do not presuppose notions of the order of ‘true’;

they are instructions for [...] uttering, instructions for carrying out syntactic transformations, [...] etc.

But the success of the ‘language-using program’ may well depend on the existence of a suitable correspondence between the words of a language and things ....

The notions of truth and reference may be of great importance in explaining the relation of language to the world

without being as central [...] as they are in [...] theories that equate understanding with knowledge of truth conditions.

Putnam, 1978 p. 100

When the utterance of a word refers to a thing,

must the utterer have knowledge of reference?

Yes

Those who communicate with words are not participants in an activity they cannot survey; they can ‘see what is going on‘.

Therefore in characterising reference, we should attempt to do so in terms of those of their mental states in virtue of which their utterances refer to things.

No

At bottom, communication with words is a matter of following rules.

This can be done without any insight into why the rules are as they are.

Therefore we mental states of communicators in virtue of which their utterances refer are unnecessary for characterising reference.

When the utterance of a word refers to a thing,

must the utterer have knowledge of reference?

Is there only the pattern of use,

or is there also justification for it?

Are there any arguments?

Why think there any such thing as knowledge of reference?

Understanding a word can’t be purely a practical ability because this would ‘render mysterious our capacity to know whether we are understanding.’

Dummett, 1991 p. 93

Fact to be explained: Communicators can know, sometimes, whether they are understanding.

Candidate explanation: Having knowledge of reference (whatever that is) can enable you to know, sometimes, that you are understanding. (And lacking knowledge of reference that you are not understanding.)

Communication by language is ‘a rational activity on the part of creatures to whom can be ascribed intention and purpose’.

We can, and should, distinguish ‘those regularities of which a language speaker [utterer], acting as a rational agent engaged in conscious, voluntary action, makes use from those that may be hidden from him.’

Dummett, 1978 p. 104

Fact to be explained: Utterers make rational, voluntary use of certain regularites while merely conforming to others.

Candidate explanation: Those regularities which arise because an utterer uses a word in accordance with her knowledge of reference are the ones she makes rational, voluntary use of.

When the utterance of a word refers to a thing,

must the utterer have knowledge of reference?

Claim:

There is such a thing as knowledge of reference; this is what justifies (or not) an utterer’s use of a word.

Argument 1:

ftbe: Communicators can know, sometimes, whether they are understanding.

e: Having knowledge of reference (whatever that is) can enable you to know, sometimes, that you are understanding. (And lacking knowledge of reference that you are not understanding.)

Argument 2:

ftbe: Utterers make rational, voluntary use of some regularites while merely conforming to others.

e: Those regularities which arise because an utterer uses a word in accordance with her knowledge of reference are the ones she makes rational, voluntary use of.

When the utterance of a word refers to a thing,

must the utterer have knowledge of reference?

Is there only the pattern of use,

or is there also justification for it?

‘There is a common-sense picture of the relation between knowledge of reference and pattern of use.

... you use the word the way you do because you know what it stands for’

Campbell, 2002 p. 4

My proposal:

1. There are multiple, internally consistent characterisations of reference.

2. If our aim were only to explain The Difference, there would be no ground for preferring one over all others.

3. But we must also explain The Justification (How does knowledge of reference cause and justify the use of a word?).