Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

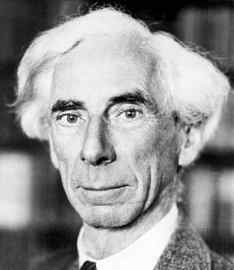

Acquaintance (Russell’s Principle)

What is acquaintance?

‘Acquaintance ... essentially consists in a relation between the mind and something other than the mind’

\citep[chapter 4]{Russell:1912ln}

Russell, 1912 Chapter 4

‘we have acquaintance with anything of which we are directly aware, without the intermediary of any process of inference or any knowledge of truths’

\citep[chapter 5]{Russell:1912ln}

Russell, 1912 chapter 5

Modes of acquaintance (?):

perception?

memory?

self-awareness?

attention?

‘knowledge by acquaintance, is essentially simpler than any knowledge of truths, and logically independent of knowledge of truths’

\citep[chapter 5]{Russell:1912ln}

Russell, 1912 chapter 5

Why care about acquaintance?

‘Every proposition which we can understand must be composed wholly of constituents with which we are acquainted’

\citep[p.~209]{Russell:1910fa}

Russell, 1910 [1963] p. 209

‘it is scarcely conceivable that we can make a judgement or entertain a supposition without knowing what it is that we are judging or supposing about.

We must attach some meaning to the words we use, if we are to speak significantly and not utter mere noise;

and the meaning we attach to our words must be something with which we are acquainted’

\citep[chapter 5]{Russell:1912ln}

Russell, 1912 chapter 5

Why do those utterances differ in that one is made true by how things are with Earth whereas the other by how things are with Mars?

Guess: There is some relation between the utterance of ‘Earth’ [the word] and Earth [the thing] in virtue of which Steve’s utterance of the sentence is about Earth rather than Mars.

Terminology: call it ‘reference’

Q: What is this relation?

Russell: For an utterance of ‘Earth’ to refer to Earth, the utterer must be acquainted with Earth. (And ...)

Russell’s claim about reference is incompatible with

(the sufficiency of) three crude theories of reference ...

Russell: For an utterance of ‘Earth’ to refer to Earth, the utterer must be acquainted with Earth. (And ...)

Causal (Kripke): For an utterance of ‘Earth’ to refer to Earth is for (a) Earth to have been baptised ‘Earth’ and (b) this utterance to be causally related in the appropriate way to that baptism event.

Russell: For an utterance of ‘Earth’ to refer to Earth, the utterer must be acquainted with Earth. (And ...)

Pragmatist: For an utterance of ‘Earth’ to refer to Earth is for this utterance to sieze the ‘interpreter’s eyes and forcibly turn them upon’ Earth.

Russell: For an utterance of ‘Earth’ to refer to Earth, the utterer must be acquainted with Earth. (And ...)

Description (nobody?): For an utterance of ‘Earth’ to refer to Earth is for (a) the speaker to have associated this utterance of ‘Earth’ with a descripton, and (b) Earth to be the thing which, uniquely, this description is true of.

Does reference require acquaintance with the referent?

My proposal:

1. There are multiple, internally consistent characterisations of reference.

2. If our aim were only to explain The Difference, there would be no ground for preferring one over all others.