Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Trading on Identity

Are senses descriptions?

Andrea is in her office speaking on the telephone to her friend Ben. As she looks out of the window, Andrea notices a man on the street below using his mobile phone. He’s not looking where he’s going; he’s about to step out in front of a bus. Andrea does not realise that this man is Ben, the friend she is speaking to. She bangs the window and waves frantically in an attempt to warn the man, but says nothing into the phone.

adapted from Richard, 1983 p. 439

He [‘the man on the street’] is in danger.

∴ He [‘the man I am speaking with’] is in danger.

valid-1 = the premises cannot be true unless the conclusion is true

valid-2 = knowledge of the premises suffices for knowledge of the conclusion

Sense is that which determines whether

such inferences are valid-2

(Campbell, 1992).

Are senses descriptions?

Three One Topics

Acquaintance

Sense

Knowledge of reference

Sense and Acquaintance

‘the normativity of the mental requires the world-involving character of the mind.’

Campbell, 1987 p. 292

‘Acquaintance ... essentially consists in a relation between the mind and something other than the mind’

\citep[chapter 4]{Russell:1912ln}

Russell, 1912 Chapter 4

‘we have acquaintance with anything of which we are directly aware, without the intermediary of any process of inference or any knowledge of truths’

\citep[chapter 5]{Russell:1912ln}

Russell, 1912 chapter 5

Modes of acquaintance (?):

perception?

memory?

self-awareness?

attention?

How might sense and acquaintance be linked?

Are senses ways of being acquainted?

‘There is a common-sense picture of the relation between knowledge of reference and pattern of use.

... you use the word the way you do because you know what it stands for’

Campbell, 2002 p. 4

‘by thinking of knowledge of reference as explained by conscious attention to the object, we can see how to reinstate the common-sense picture’

Campbell, 2002 p. 4

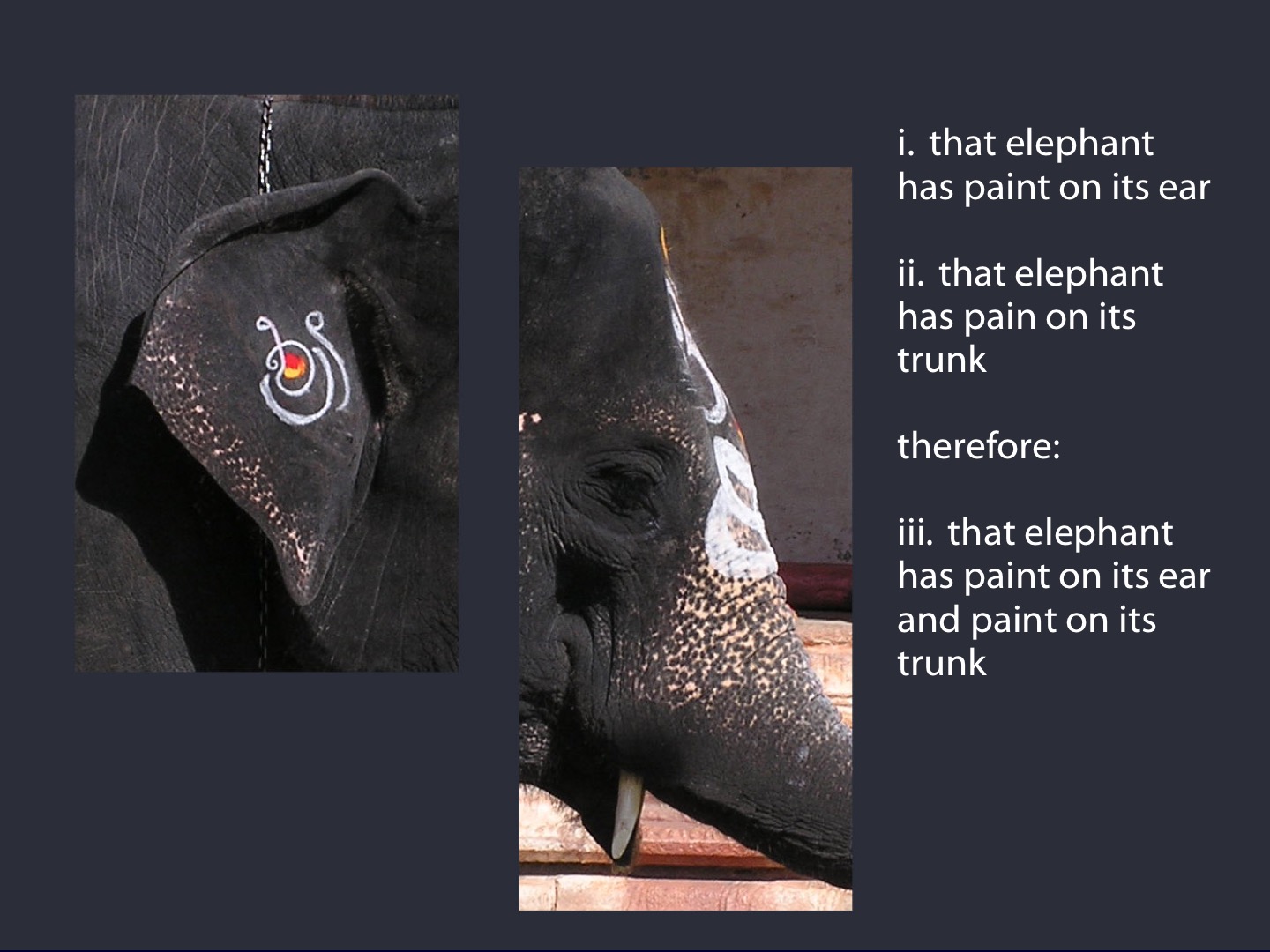

There are acts of attention (e.g. tracking an elephant walking ahead).

Re-identification is needed only when there are two acts of attention.

Two thoughts about this elephant can depend on one act of attention.

When this happens, trading on identity is legitimate.

Sense is that, sameness of which makes trading on identity legitimate.

When two thoughts about this elephant depend on one act of attention, they involve a single sense.

?

same act of attention -> same sense

When two utterances of a word (or phrase) are controlled by a single act of attention, they have the same sense.

‘the notion of conscious attention to an object has an explanatory role to play: it has to explain how it is that we have knowledge of the reference of a demonstrative.

‘This means that conscious attention to an object must be thought of as more primitive than thought about the object.

‘It is a state more primitive than thought about an object, to which we can appeal in explaining how it is that we can think about the thing’

Campbell, 2002 p. 45

‘We might argue that the mode of presentation of a perceptually demonstrated object has to be characterized

... in terms of the property that the subject uses to select that object perceptually.

Sameness of mode of presentation is the same thing as sameness of the property on the basis of which the object is selected;

difference of mode of presentation is the same thing as difference of the property on the basis of which the object is selected.’

Campbell, 2011 p. 341

?

same act of attention -> same sense

When two utterances of a word (or phrase) are controlled by a single act of attention, they have the same sense.

✗

What is sense supposed to do?

1. Sense explains the difference in informativeness between the utterance of ‘Charly is Charly’ and ‘Charly is Samantha’.

2. Sense determines reference.

3. A statement showing the sense of a name specifies what you need to know about the utterance of a name in order to understand it.

?

same act of attention -> same sense

When two utterances of a word (or phrase) are controlled by a single act of attention, they have the same sense.

The sense of an utterance of a word (or phrase)

is what you know when you

have knowledge of reference.

✗

ftbe:

Communicators can know, sometimes,

whether they are understanding.

How?

Utterers make rational, voluntary use of some regularites

while merely conforming to others.

How is this possible?

∴ there is a mental state of the utterer in virtue of which her utterance refers to ‘Earth’.

Call this mental state ‘knowledge of reference’.

same act of attention -> same sense

within a person ✓

between people (an utter and her audience) ✗

Contrast descriptions: understanding you means associating the same description with the word.

Conscious attention isn’t enough for understanding because ‘it can happen that I am consciously attending to the building to which you are referring, even though I do not realize that it is the building to which you are referring. Conscious attention to the building is not in itself an understanding of your remark: I have to make a link between that conscious attention and the demonstrative you use [see chapters 1-2 and 6-7]’

Campbell, 2002 p. 5

?

same act of attention -> same sense

When two utterances of a word (or phrase) are controlled by a single act of attention, they have the same sense.

**** TODO Summary

NEXT : ensuring matching acts of attention (why might you point, or move next to someone when using a perceptual demonstrative?)

The Picture

What are the facts to be explained?

1. This utterance of ‘Ayesha smells’ depends for its truth on how Ayesha is, unlike that utterance of ‘Beatrice smells’. Why?

2. This utterance of ‘Charly is Charly’ was less revelatory than that utterance of ‘Charly is Samantha’. Why?

3. Humans successfully achieve ends by uttering words. How?

4. Communicators can know, sometimes, whether they are understanding. How?

5. Utterers make rational, voluntary use of some regularites while merely conforming to others. How is this possible?

The Picture

#1 ∴ there is a word-thing relation; call it ‘reference’.

Reference, if it exists, must explain #1 and #3.

#2 ∴ meaning isn’t only reference; call the aspect which explains #2 ‘sense’.

Knowledge of reference, if it exists must explain #4 and #5.

The sense of an utterance is what you know when you have knowledge of reference.

Sometimes the sense of an utterance is a description.

But not always.

Sometimes the sense of an utterance is individuated by an act of attention.

conclusion: some senses are descriptions, others are modes of acquaintance.

Massive Reduplication

If your utterance of a word refers to a thing, then ...

1. you must be acquainted with that thing;

2. you must either be acquainted with it or else know it by description; or

3. you need neither acquintace nor knowledge by description.

Russell’s idea:

Reference requires acquaintance knowledge of reference

Objection: in uttering ‘Julius Caesar drank the Rubicon’, I refered to Julius despite not being acquainted with him.

Reply: ‘Julius Caesar’ is actually a quantifier phrase (specifically, a description), so I did not refer.

Objection: rigid designators (Kripke)

Reply: descriptions can be rigidified

Objection: ...

...

For all we know, a distant region of the universe may contain qualitatively indistinguisable duplicates of everything here.

Therefore: For all we know, even our most elaborate descriptions may fail to pick out individuals.

Therefore: When we rely on descriptions, we may fail to single out a unique object for all we know.

Therefore: If we relied only on descriptions, we may, for all we know, never single out a unique object.

But: We know that our utterances sometimes succeed in singling out a unique object.