Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

‘meaning is normative’

‘Whatever its pedigree, and however popular and suggestive it might seem, a slogan it remains.’

Whiting, 2016 p. 221

How to get past sloganeering?

First attempt

For any S, x: if ‘red’ means red, it is correct for S to apply ‘red’ to x if and only if x is red.

‘All parties, even the staunchest critics of Normativism, would agree that [this] is platitudinous’

Whiting, 2016 p. 222

Second attempt:

For any S, x: if ‘red’ means red, S ought pro tanto not to (apply ‘red’ to x) if and only if x is not red.

Third attempt:

For any S, x: if S intends by uttering ‘red’ to mean red, S ought not to (apply ‘red’ to x) if and only if x is not red.

‘instrumental normativity ... is not what the Normativist is after.’

Whiting, 2016 p. 222

“The intention to be taken to mean what one wants to be taken to mean is, it seems to me, so clearly the only aim that is common to all verbal behaviour that it is hard for me to see how anyone can deny it.”

This aim “assumes the notion of meaning”, but

“it provides a purpose which any speaker must have in speaking, and thus constitutes a norm against which speakers and others can measure the success of their verbal behavior.”

Davidson 1994, p. 11

Third attempt:

For any S, x: if S intends by uttering ‘red’ to mean red, S ought not to (apply ‘red’ to x) if and only if x is not red.

‘instrumental normativity ... is not what the Normativist is after.’

Whiting, 2016 p. 222

instrumental normativity?

Analogy:

Intention 2: To save the zoo visitor from attack

Intention 1: by hitting the escaped gorilla with a tranquiliser dart.

Communication

Intention 1: To communicate that I don’t want coffee

Intention 2: by being understood as saying that my life is not entirely breakfastless.

‘meaning is normative’

‘Whatever its pedigree, and however popular and suggestive it might seem, a slogan it remains.’

Whiting, 2016 p. 221

In what sense, if any, is meaning normative?

Sense and Descriptions

Samantha is Samantha

Samantha is Charly

Samantha Caine

Suburban homemaker and the ideal mom to her 8 year old daughter Caitlin. She lives in a New England small town, teaches in a local school and makes the best Rice Krispie treats in town.

Charly Baltimore

a highly trained secret agent and cold-blooded killer involved in the government's most unscrupulous affairs.

?

The sense of my utterance of ‘Charly Baltimore’ is this description:

the highly trained secret agent suffering from amnesia in New England.

The sense of my utterance of ‘Samantha Caine’ is this description:

the New England teacher with an 8 year old daughter who makes the best Rice Krispie treats in town.

‘all that anyone has been able to think of is that different [i.e. senses] are a matter of different descriptions being associated with the signs.

Some other views have been tried ... But these ideas have not been found compelling’

Campbell, 2011 p. 340

?

The sense of my utterance of ‘Charly Baltimore’ is this description:

the highly trained secret agent suffering from amnesia in New England.

The sense of my utterance of ‘Samantha Caine’ is this description:

the New England teacher with an 8 year old daughter who makes the best Rice Krispie treats in town.

Contrast that utterance of ‘Charly is Charly’ with the utterance ‘Charly is Samantha’

ftbe: These may differ in informativeness.

Terminology: call whatever aspect of meaning explains the difference ‘sense’.

The sense of an utterance of a word (or phrase)

is what you know when you

have knowledge of reference.

✓

Contrast that utterance of ‘Charly is Charly’ with the utterance ‘Charly is Samantha’

ftbe: These may differ in informativeness.

Terminology: call whatever aspect of meaning explains the difference ‘sense’.

?

The sense of my utterance of ‘Charly Baltimore’ is this description:

the highly trained secret agent suffering from amnesia in New England.

The sense of my utterance of ‘Samantha Caine’ is this description:

the New England teacher with an 8 year old daughter who makes the best Rice Krispie treats in town.

✓

ftbe:

Communicators can know, sometimes,

whether they are understanding.

How?

Utterers make rational, voluntary use of some regularites

while merely conforming to others.

How is this possible?

∴ there is a mental state of the utterer in virtue of which her utterance refers to ‘Earth’.

Call this mental state ‘knowledge of reference’.

?

The sense of my utterance of ‘Charly Baltimore’ is this description:

the highly trained secret agent suffering from amnesia in New England.

The sense of my utterance of ‘Samantha Caine’ is this description:

the New England teacher with an 8 year old daughter who makes the best Rice Krispie treats in town.

?

The sense of my utterance of ‘Charly Baltimore’ is this description:

the highly trained secret agent suffering from amnesia in New England.

The sense of my utterance of ‘Samantha Caine’ is this description:

the New England teacher with an 8 year old daughter who makes the best Rice Krispie treats in town.

✓

‘There is a common-sense picture of the relation between knowledge of reference and pattern of use.

... you use the word the way you do because you know what it stands for’

Campbell, 2002 p. 4

?

The sense of my utterance of ‘Charly Baltimore’ is this description:

the highly trained secret agent suffering from amnesia in New England.

The sense of my utterance of ‘Samantha Caine’ is this description:

the New England teacher with an 8 year old daughter who makes the best Rice Krispie treats in town.

Are senses descriptions?

Example (use 1): “A bear is about to attack me”

contrast: ‘A bear is about to attach Steve’

The sense of ‘I’ cannot be the sense of ‘Steve’.

Example (use 2): “A bear is about to attack me”

“When you and I entertain the sense of "A bear is about to attack me," we behave similarly. We both roll up in a ball and try to be as still as possible …

“When you and I both apprehend the thought that I am about to be attacked by a bear, we behave differently. I roll up in a ball, you run to get help.”

Perry, 1977 p. 494

Could the sense ‘I’ be a description?

Are senses descriptions?

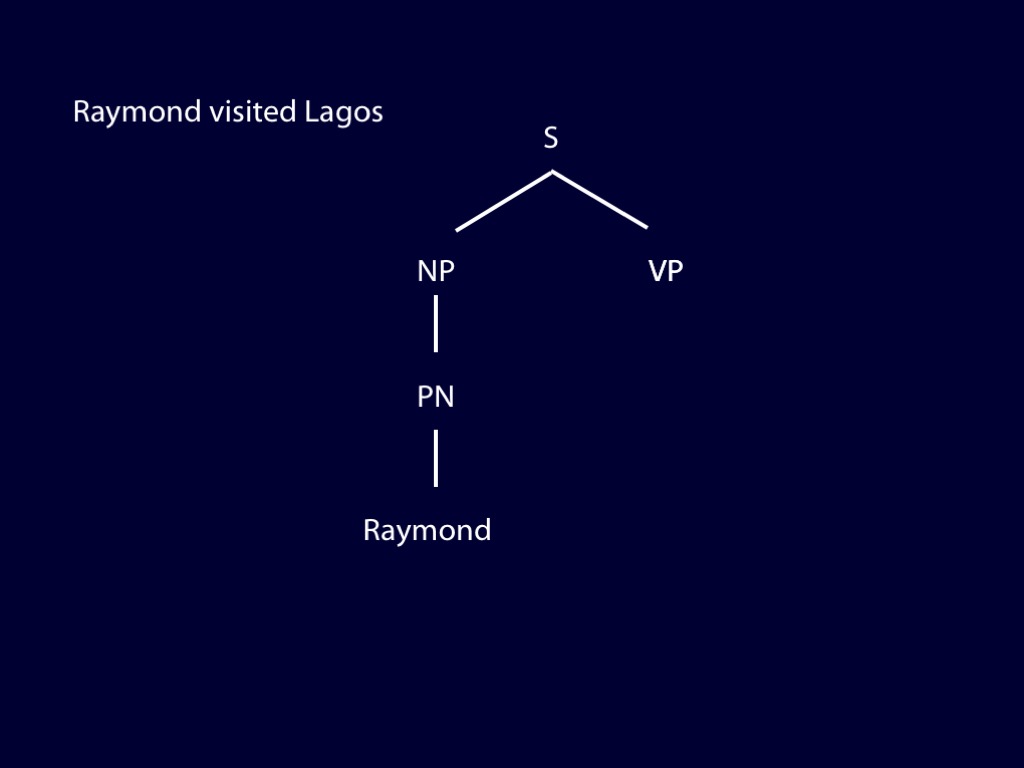

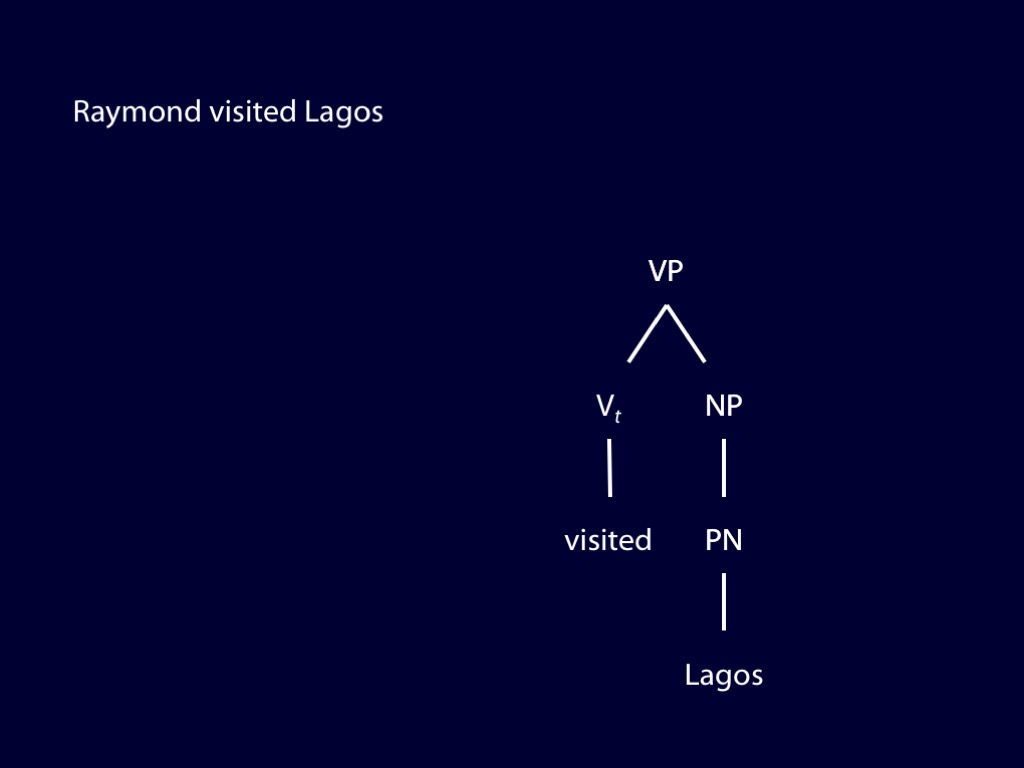

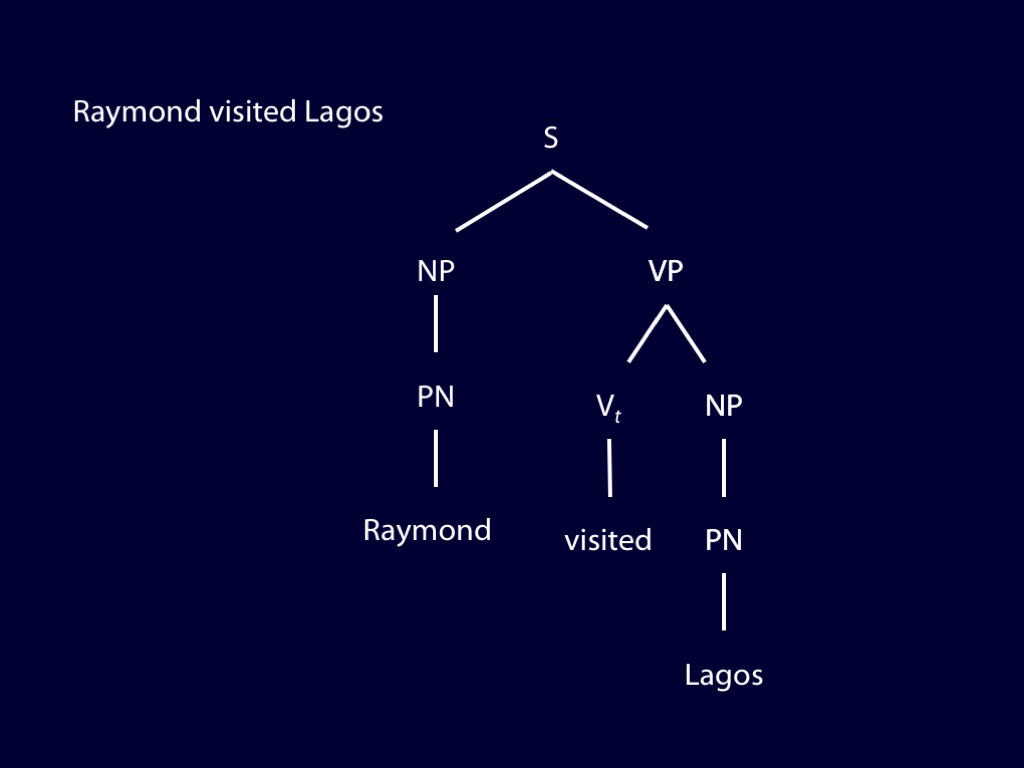

Syntax

What features are characteristic of language?

S’s 13:11 utterance of ‘Earth is being warmed by human activity’ is true exactly if Earth is being warmed by human activity.

S’s 13:11 utterance of ‘Mars is being warmed by human activity’ is true exactly if Mars is being warmed by human activity.

‘A semantic theory for a particular natural language will … articulate an assignment of meanings to sentences …

It will also display just how the sentences come to have the meanings they do, given their construction out of more basic constituents: it will reveal semantic structure. …

The recurrent contribution that a constituent expression makes to the meanings of several sentences in which it occurs will be revealed in the use of … the principle assigning a semantic property to that expression … in the derivations of meaning assignments for all those sentences”

(Davies 1986: 130).

How is constructing a semantic theory possible?

obstacle: there are uncountably many sentences.

[Compositionality]

The meaning of a sentence (and of any complex expression) is fully determined by its structure and the meanings of its constituent words.

Semantics requires syntax.

Contrast to be explained:

‘Music makes swans purple above’ is an English sentence.

‘Water swans in swim’ is not an English sentence.

What does a syntact theory reveal?

How can we discover the syntactic structure of a sentence you utter?

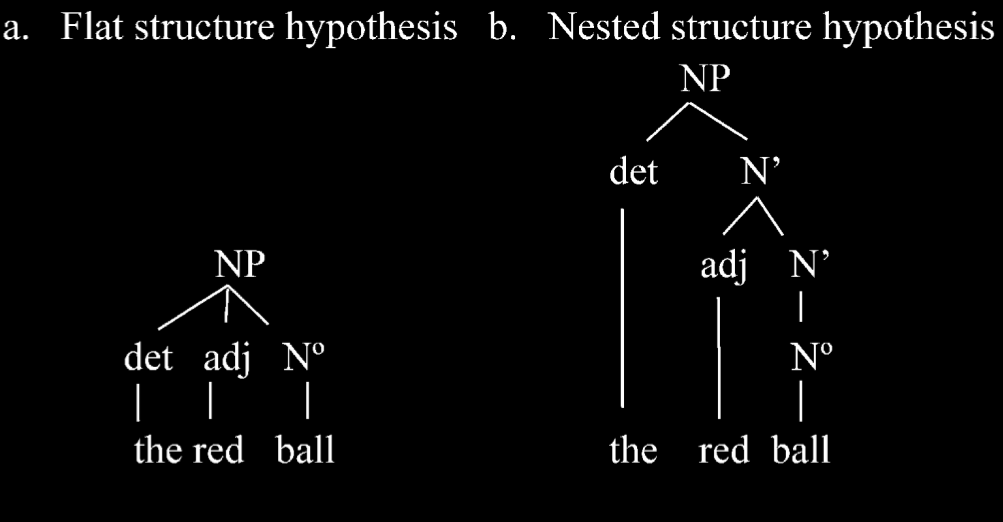

the red ball

‘I’ll play with this red ball and you can play with that one.’

Lidz et al (2003)

- \item ‘red ball’ is a constituent on (b) but not on (a)

- \item anaphoric pronouns can only refer to constituents

- \item In the sentence ‘I’ll play with this red ball and you can play with that one.’, the word ‘one’ is an anaphoric prononun that refers to ‘red ball’ (not just ball). \citep{lidz:2003_what,lidz:2004_reaffirming}.

How can we discover the syntactic structure of a sentence you utter?

Two Questions

What are the syntactic structures of those sentences?

What is the relation between these structures and those who utter them?

How is constructing a semantic theory possible?

obstacle: there are uncountably many sentences.

[Compositionality]

The meaning of a sentence (and of any complex expression) is fully determined by its structure and the meanings of its constituent words.

Summary

- The aim of semantics is to explain productivity and systematicity of language.

- We need semantics (not just syntax and pragmatics) in explaining how communication by language succeeds because languages are productive and systematic.

- Semantic theories attempt to explain systematicity and productivity by identifying compositional structure in languages.

- Success depends on discovering syntactic structures.

- Identifying compositional structure requires assigning semantic values to fragments of sentences; part of this is provided by the theory of reference.

conclusion

Why?

Some of the things you utter

are true (or false)

in virtue of how things are with Ayesha.