Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Please write down the answers (Y/N) to each of the following three questions ...

1. Can a woman marry her daughter’s boyfriend?

2. Can a man marry his sister’s mother?

3. Can a man marry his widow’s sister?

... save your answers for later.

Linking Meaning and Reference: Compositionality

Why?

Some of the things you utter

are true (or false)

in virtue of how things are with Ayesha.

Because your utterances of ‘Ayesha’ refer to Ayesha.

But what about meaning?

‘entities such as meanings ...

are not of independent interest’

Davidson, 1974 p. 154

Why suppose that sentences have meanings?

facts to be explained

If someone utters a sentence and you understand her, then you will likely understand others when they utter that sentence. And conversely.

If a sentence is used to communicate something in one situation, then it can typically be used to communicate much the same thing in another situation.

attempted explanation

(guess)

There are some things and nearly every sentence is related to a different thing.

Communicators often know which thing is related to which sentence.

This knowledge (is part of what) enables them to understand utterances of those sentences.

termiology

Call these things ‘meanings’.

How is the idea that

sentences have meanings

related to the idea that

utterances refer to things?

facts to be explained

[Systematicity] ‘there are definite and predictable patterns among the sentences [utterances of which] we understand’ (Szabó, 2004).

[Productivity] communicators can understand utterances of an indefinitely large range of sentences we have never heard before.

attempted explanation

Words have meanings (which are their referents senses).

[Compositionality] The meaning of a sentence (and of any complex expression) is fully determined by its structure and the meanings of its constituent words.

How is the idea that

sentences have meanings

related to the idea that

utterances refer to things?

A theory of reference

would be part of a

theory of meaning.

aside on method

What is with all the facts to be explained?

the manifest image

‘the framework in terms of which we ordinarily observe and explain our world’

‘the framework in terms of which man [sic] came to be aware of himself as man-in-the-world’

Sellars, deVries

the scientific image

... allows ‘the addition to the framework of new concepts of basic objects by means of theoretical postulation’.

This is the world of philosophers.

This is not the world of philosophers.

‘the aim of bringing all of one’s own opinions into equilibrium’

‘the [...] aim in philosophy of discovering the equilibrium positions that can withstand examination’

Beebee, 2017

110th Presential Address, Aristotelian Society

philosophical

methods

informal observation,

guesswork (‘intuition’),

imagining counterfactual situations

(‘thought experiments’),

reasoning,

& theoretical elegance

Philosophers use informal observation, imagination and their knowledge of scientific discoveries to ask questions;

they use reasoning to identify inconsistent patterns of answers;

and they make guesses about roughly what the answers might be (model sketches),

with the aim of facilitating discoveries.

Knowledge of Reference and Pragmatics

Reference

Steve’s 13:11 utterance of ‘Earth’ refers to Earth

Knowledge of Reference : what is meant?

1. Steve knows Earth (either by acquiantance or description).

2. Steve knows that his 13:11 utterance of ‘Earth’ refers to Earth.

3. There is a state of Steve’s mind in virtue of which his 13:11 utterance of ‘Earth’ refers to Earth.

Q1 What, if anything, is that state of mind?

Q2 Why think there any such thing as this state of mind?

At bottom, communication with words is a matter of following rules.

This can be done without any insight into why the rules are as they are.

Therefore mental states of communicators in virtue of which their utterances refer are unnecessary for characterising reference.

cf Putnam 1978

‘I’ve had a great evening. This wasn’t it.’

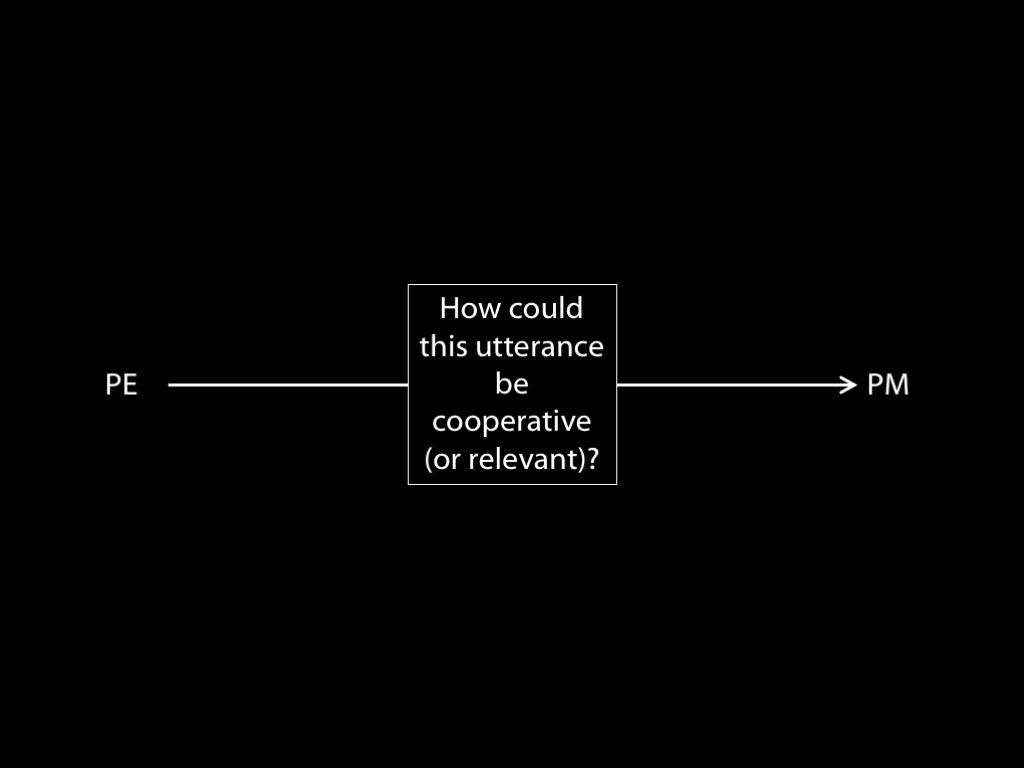

MS, the meaning of the sentence;

PE, the proposition expressed; and

PM, the proposition meant.

Neale, 1990 p. 75

I have had breakfast.

I have had a kidney removed.

I have had fermented fish for breakfast.

I have had a great evening.

Among utterances of these sentences,

there can be is variation in the PM

although Compositionality does not permit corresponding variation in MS.

Given that MS is a function from contexts of utterance to propositions,

the values of this function will not typically be a PM.

Terminology: Call the value of MS in a given context of utterance the ‘proposition expressed (PE)’.

MS, the meaning of the sentence;

PE, the proposition expressed; and

PM, the proposition meant.

Neale, 1990 p. 75

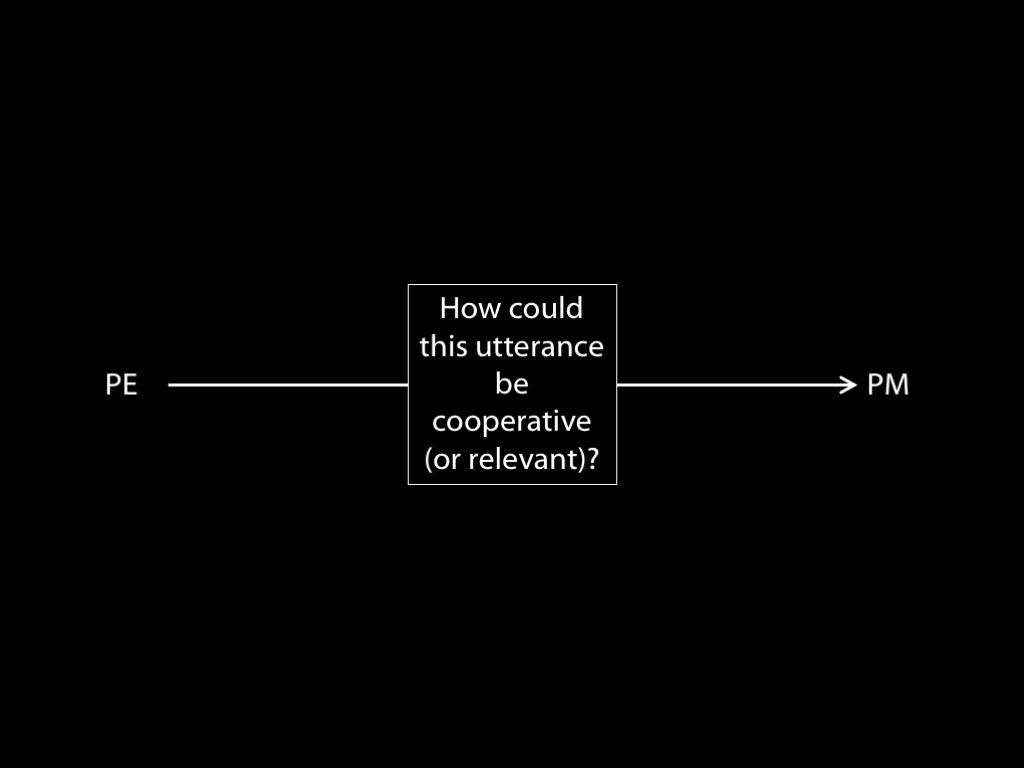

How do you get from PE to PM?

reasoning about cooperation (Grice)

searching for relevance (Sperber & Wilson)

At bottom, communication with words is a matter of following rules.

This can be done without any insight into why the rules are as they are.

Therefore mental states of communicators in virtue of which their utterances refer are unnecessary for characterising reference.

cf Putnam 1978

Two Arguments

1. Communication with words involves successful communication of a PM.

2. Which PMs an utterance communicates depends on context in arbitrarily complex, uncodifiable ways.

Therefore,

3. communication with words cannot be entirely a mechanical, script-following, rule-bound

activity.

1. Arriving at a PM depends on taking the PE and searching for cooperation or relevance.

Therefore,

2. communication requires representing PEs, which requires knowledge of reference.

Reference

Steve’s 13:11 utterance of ‘Earth’ refers to Earth

Knowledge of Reference : what is meant?

1. Steve knows Earth (either by acquiantance or description).

3. There is a state of Steve’s mind in virtue of which his 13:11 utterance of ‘Earth’ refers to Earth.

Q1 What, if anything, is that state of mind?

Q2 Why think there any such thing as this state of mind?

When the utterance of a word refers to a thing,

must the utterer have knowledge of reference?

What is the relation between

an utterance of a word (or phrase)

and a thing

when the utterance refers to the thing?

It is a psychological relation.

Lexical Innovation

Suppose there are two people and a word and that when communicating by language the second person once uses the word with the same meaning the first person once used it with, and that the sameness of meaning is non-accidental.

Is the existence of such a pair of people and a word necessary for there to be linguistic communication?

“It is a convention of English that ‘red’ in its most basic, literal sense, is correctly predicated only of things which are red. Speakers of English who are credited with an understanding of ‘red’ in its most basic and literal sense are thereby credited, inter alia, with the intention to uphold this pattern of predication as a matter of convention”

Wright, 1986 p. 220

“The role of symbols in language is evident: the meaning of a word or phrase is fixed (at least in part) by the conventions or rules that govern its use”

Hookway, 2000 p. 98

“A language is a set of historically evolved social conventions by means of which intentional agents attempt to manipulate one an¬other’s attention”

Tomasello 2001, p. 1120

1. Can a woman marry her daughter’s boyfriend?

2. Can a man marry his sister’s mother?

3. Can a man marry his widow’s sister?

“N. N. is in negotiations with the hostages [meaning captors]” (BBC Radio 4, News at 5pm, 12/11/03).

“When an aircraft crashes, where should the survivors be buried?” (Sanford 2002: 193)

lexical innovation

... often depends on facts about how words have been used in the past

... can result in meanings that persist.

Nouning] “you will you be ... my total big disorientator” (Karl Hyde, “Mmm Skyscraper I Love You”).

Malaprop] “Charles was wearing an old-fashioned mourning suit with a silk caveat around his neck and a monocycle in one eye.”

Joyce] “The Gracehoper was always jigging ajog, hoppy on akkant of his joyicity” (Finnegans Wake 408.22).

Malaprop and other forms of lexical innovation are “in the nature of things, atypical cases: if taken as a prototype for linguistic communication, they prompt the formulation of an incoherent theory”

Dummett, 1986 p. 472

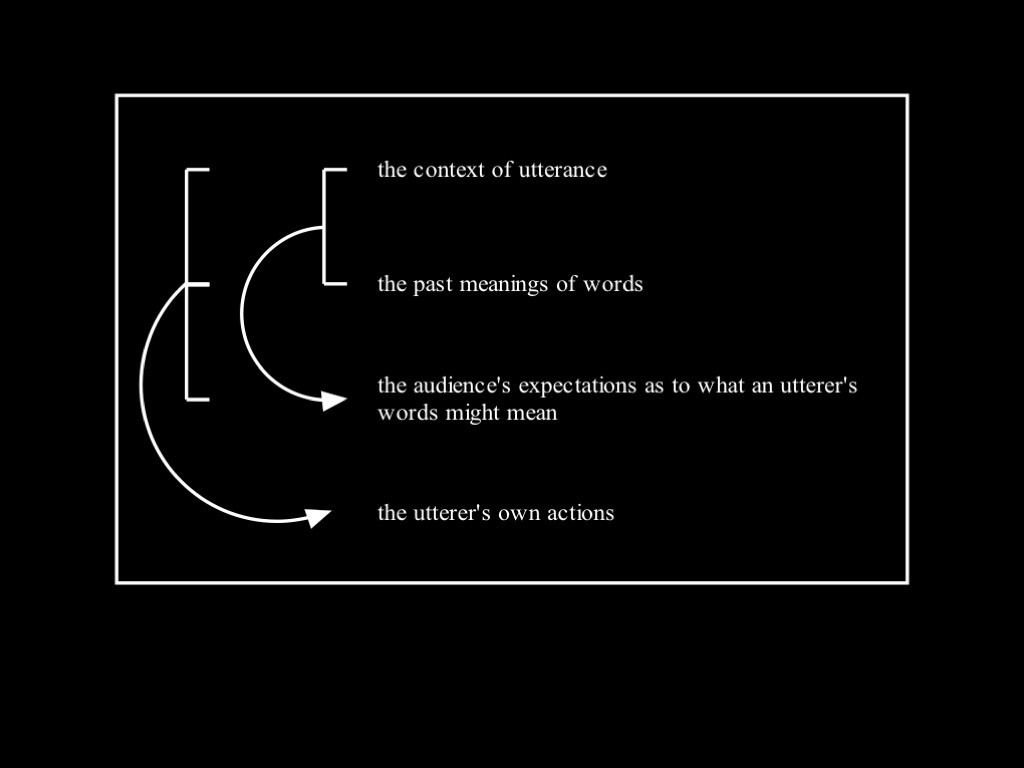

1. Conventions are at most indirectly relevant to determining what utterances mean (the PE).

2. Any successful use of a word can establish expectations as to future meanings.

3. Successful communication involves creating and violating expectations no less than it involves conforming to them.

Sense and Descriptions

Samantha is Samantha

Samantha is Charly

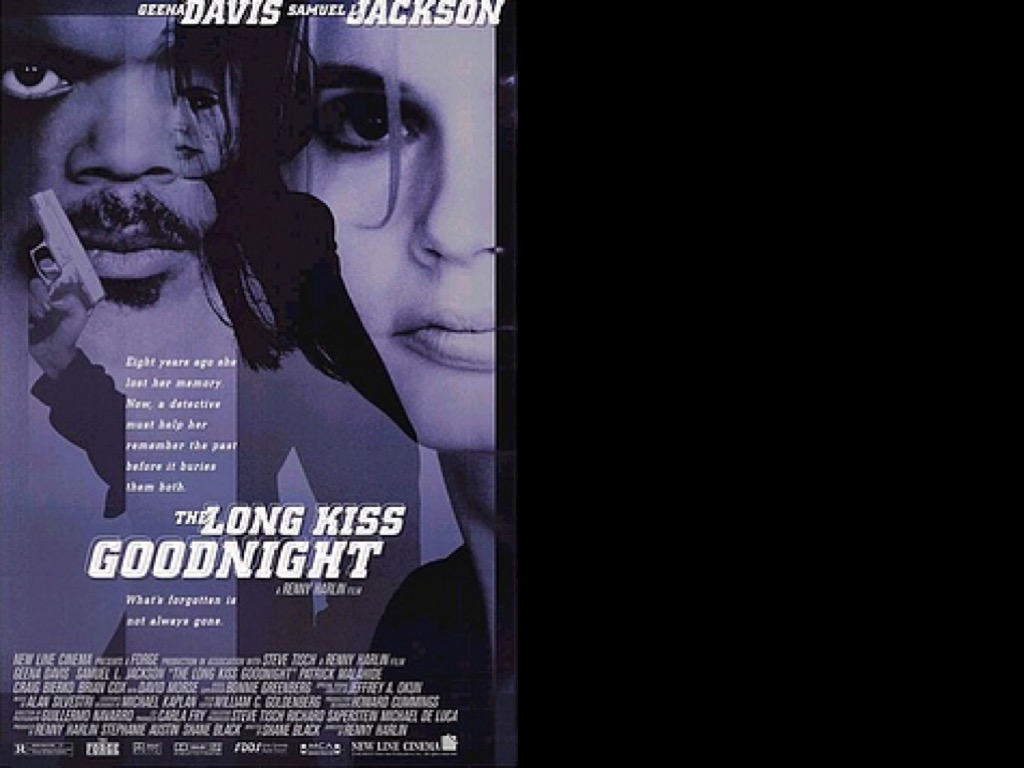

Samantha Caine

Suburban homemaker and the ideal mom to her 8 year old daughter Caitlin. She lives in a New England small town, teaches in a local school and makes the best Rice Krispie treats in town.

Charly Baltimore

a highly trained secret agent and cold-blooded killer involved in the government's most unscrupulous affairs.

?

The sense of my utterance of ‘Charly Baltimore’ is this description:

the highly trained secret agent suffering from amnesia in New England.

The sense of my utterance of ‘Samantha Caine’ is this description:

the New England teacher with an 8 year old daughter who makes the best Rice Krispie treats in town.

‘all that anyone has been able to think of is that different [i.e. senses] are a matter of different descriptions being associated with the signs.

Some other views have been tried ... But these ideas have not been found compelling’

Campbell, 2011 p. 340

?

The sense of my utterance of ‘Charly Baltimore’ is this description:

the highly trained secret agent suffering from amnesia in New England.

The sense of my utterance of ‘Samantha Caine’ is this description:

the New England teacher with an 8 year old daughter who makes the best Rice Krispie treats in town.

Contrast that utterance of ‘Charly is Charly’ with the utterance ‘Charly is Samantha’

ftbe: These may differ in informativeness.

Terminology: call whatever aspect of meaning explains the difference ‘sense’.

The sense of an utterance of a word (or phrase)

is what you know when you

have knowledge of reference.

✓

Contrast that utterance of ‘Charly is Charly’ with the utterance ‘Charly is Samantha’

ftbe: These may differ in informativeness.

Terminology: call whatever aspect of meaning explains the difference ‘sense’.

?

The sense of my utterance of ‘Charly Baltimore’ is this description:

the highly trained secret agent suffering from amnesia in New England.

The sense of my utterance of ‘Samantha Caine’ is this description:

the New England teacher with an 8 year old daughter who makes the best Rice Krispie treats in town.

✓

ftbe:

Communicators can know, sometimes,

whether they are understanding.

How?

Utterers make rational, voluntary use of some regularites

while merely conforming to others.

How is this possible?

∴ there is a mental state of the utterer in virtue of which her utterance refers to ‘Earth’.

Call this mental state ‘knowledge of reference’.

?

The sense of my utterance of ‘Charly Baltimore’ is this description:

the highly trained secret agent suffering from amnesia in New England.

The sense of my utterance of ‘Samantha Caine’ is this description:

the New England teacher with an 8 year old daughter who makes the best Rice Krispie treats in town.

?

The sense of my utterance of ‘Charly Baltimore’ is this description:

the highly trained secret agent suffering from amnesia in New England.

The sense of my utterance of ‘Samantha Caine’ is this description:

the New England teacher with an 8 year old daughter who makes the best Rice Krispie treats in town.

✓

‘There is a common-sense picture of the relation between knowledge of reference and pattern of use.

... you use the word the way you do because you know what it stands for’

Campbell, 2002 p. 4

?

The sense of my utterance of ‘Charly Baltimore’ is this description:

the highly trained secret agent suffering from amnesia in New England.

The sense of my utterance of ‘Samantha Caine’ is this description:

the New England teacher with an 8 year old daughter who makes the best Rice Krispie treats in town.

Are senses descriptions?

Example (use 1): “A bear is about to attack me”

contrast: ‘A bear is about to attach Steve’

The sense of ‘I’ cannot be the sense of ‘Steve’.

Example (use 2): “A bear is about to attack me”

“When you and I entertain the sense of "A bear is about to attack me," we behave similarly. We both roll up in a ball and try to be as still as possible …

“When you and I both apprehend the thought that I am about to be attacked by a bear, we behave differently. I roll up in a ball, you run to get help.”

Perry, 1977 p. 494

Could the sense ‘I’ be a description?

Are senses descriptions?

Trading on Identity

Are senses descriptions?

Andrea is in her office speaking on the telephone to her friend Ben. As she looks out of the window, Andrea notices a man on the street below using his mobile phone. He’s not looking where he’s going; he’s about to step out in front of a bus. Andrea does not realise that this man is Ben, the friend she is speaking to. She bangs the window and waves frantically in an attempt to warn the man, but says nothing into the phone.

adapted from Richard, 1983 p. 439

He [‘the man on the street’] is in danger.

∴ He [‘the man I am speaking with’] is in danger.

valid-1 = the premises cannot be true unless the conclusion is true

valid-2 = knowledge of the premises suffices for knowledge of the conclusion

Sense is that which determines whether

such inferences are valid-2

(Campbell, 1992).

Are senses descriptions?

Three One Topics

Acquaintance

Sense

Knowledge of reference

Sense and Acquaintance

‘the normativity of the mental requires the world-involving character of the mind.’

Campbell, 1987 p. 292

‘Acquaintance ... essentially consists in a relation between the mind and something other than the mind’

\citep[chapter 4]{Russell:1912ln}

Russell, 1912 Chapter 4

‘we have acquaintance with anything of which we are directly aware, without the intermediary of any process of inference or any knowledge of truths’

\citep[chapter 5]{Russell:1912ln}

Russell, 1912 chapter 5

Modes of acquaintance (?):

perception?

memory?

self-awareness?

attention?

How might sense and acquaintance be linked?

Are senses ways of being acquainted?

‘There is a common-sense picture of the relation between knowledge of reference and pattern of use.

... you use the word the way you do because you know what it stands for’

Campbell, 2002 p. 4

‘by thinking of knowledge of reference as explained by conscious attention to the object, we can see how to reinstate the common-sense picture’

Campbell, 2002 p. 4

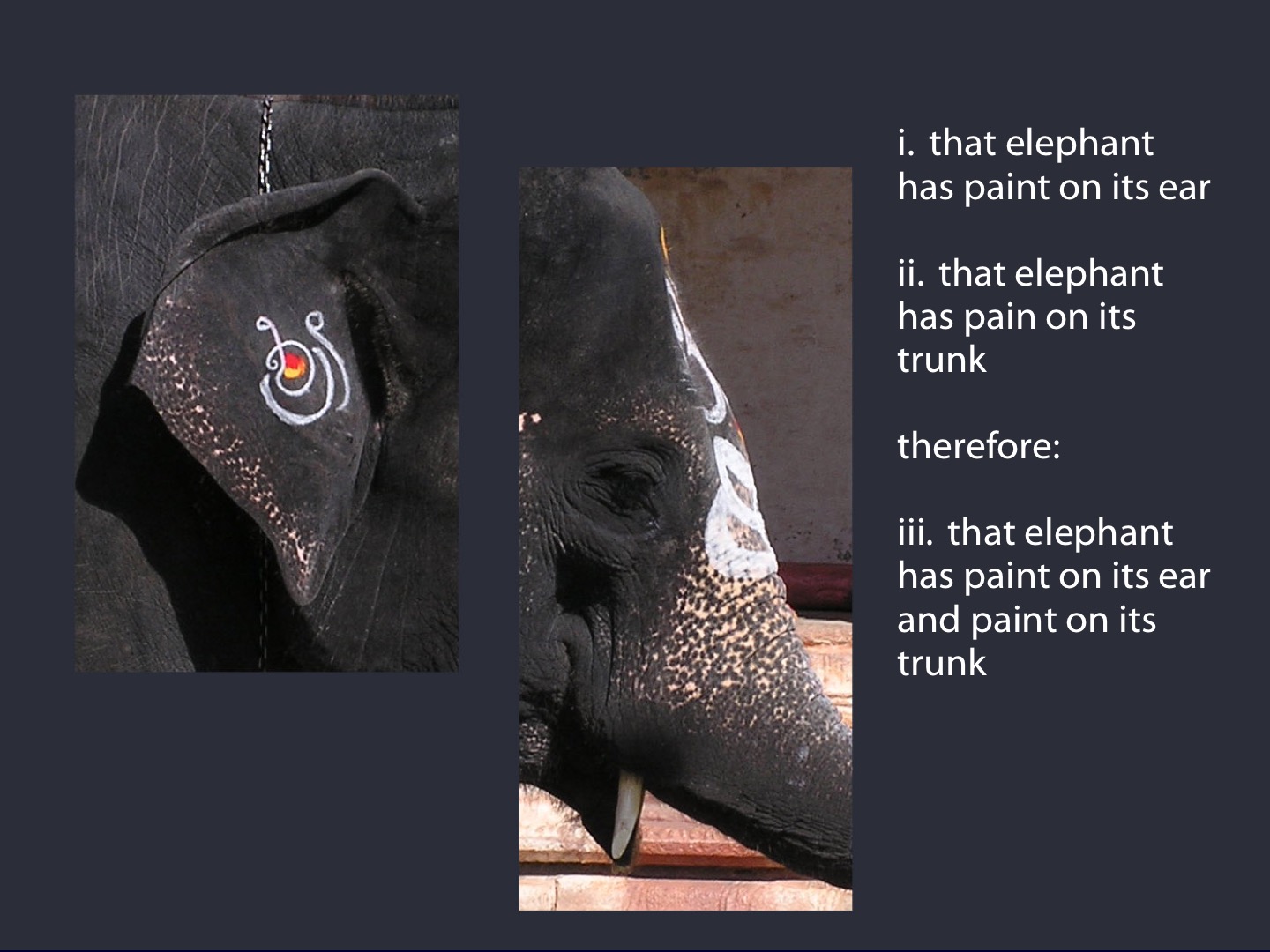

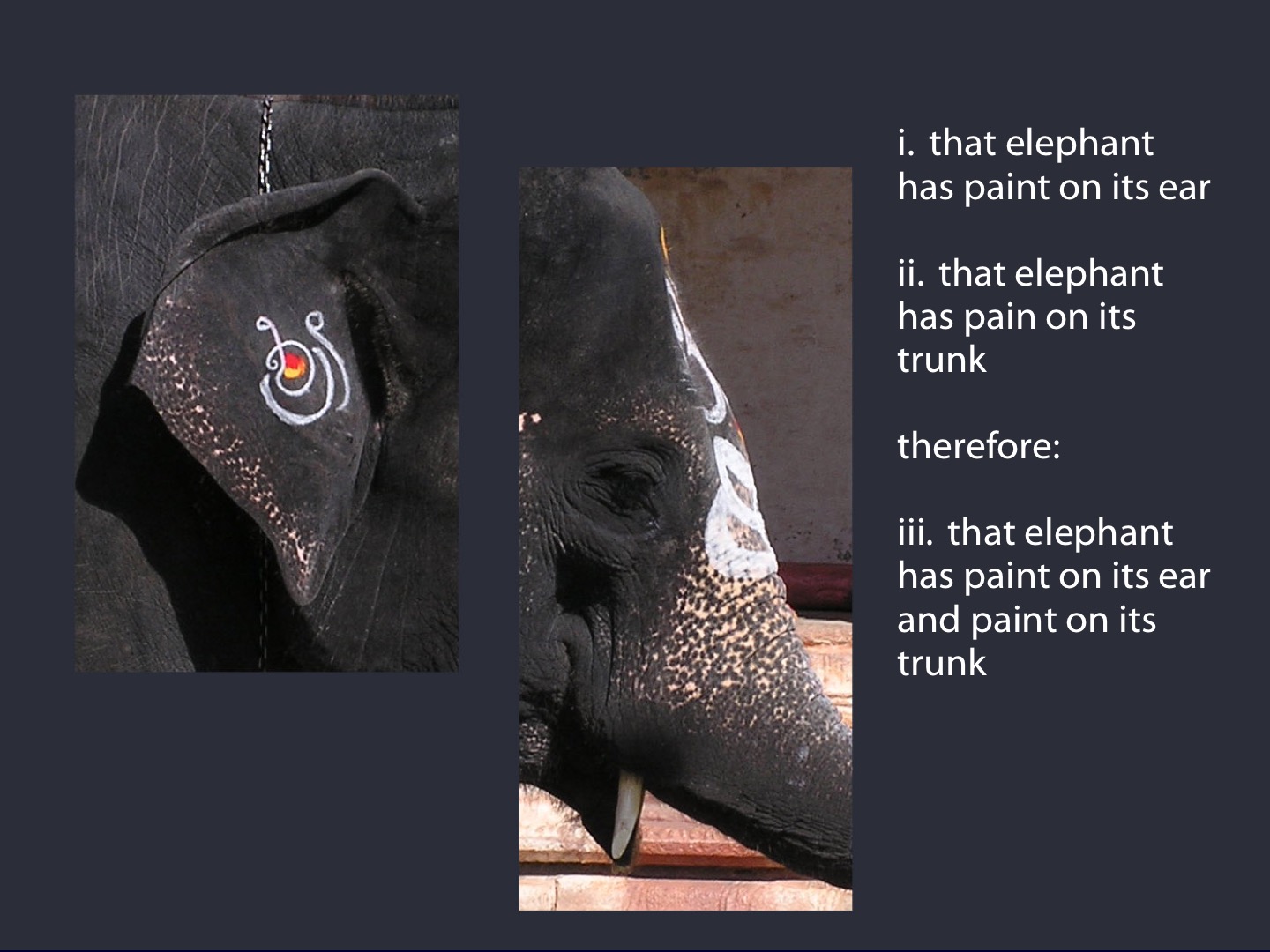

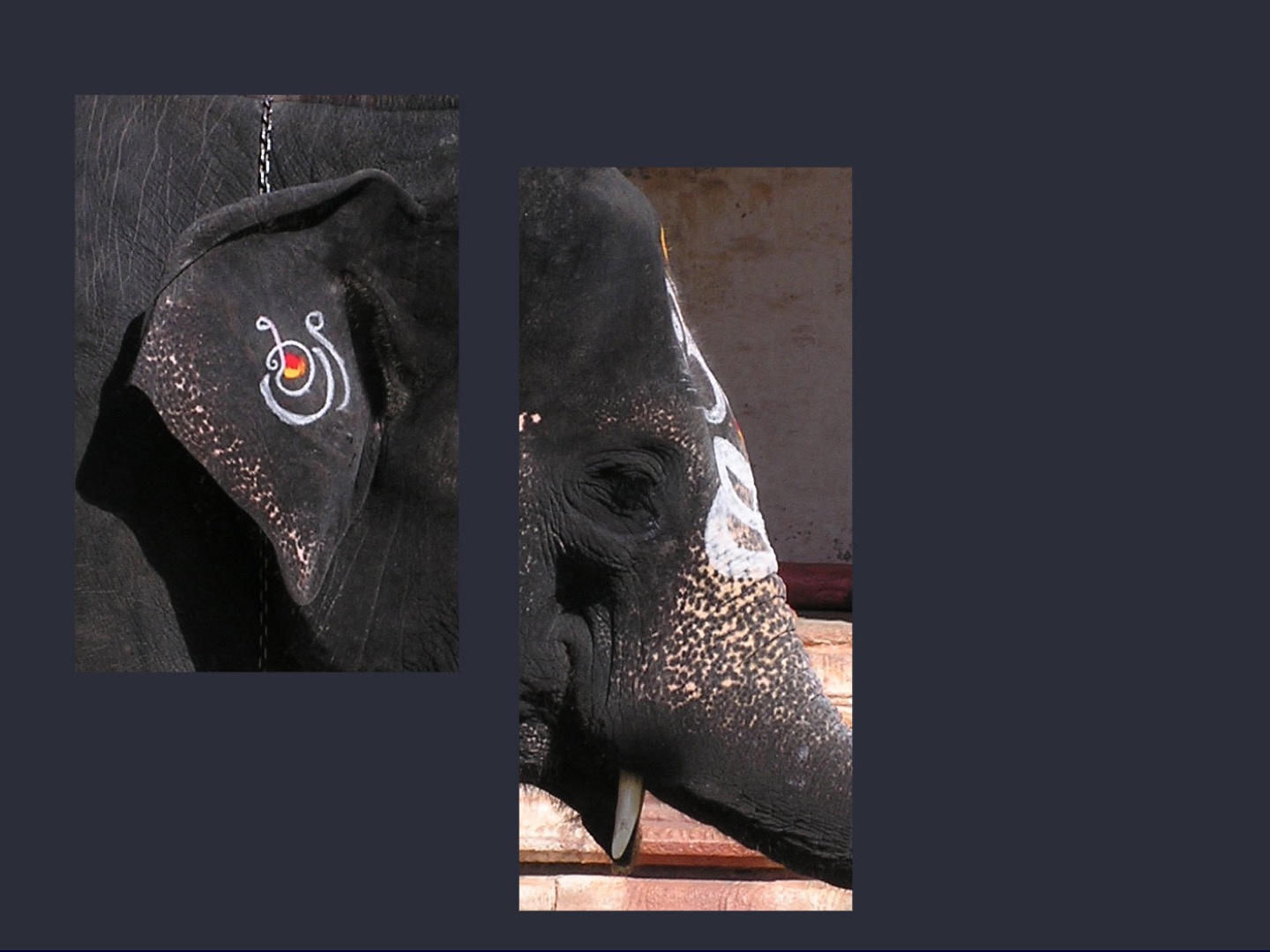

There are acts of attention (e.g. tracking an elephant walking ahead).

Re-identification is needed only when there are two acts of attention.

Two thoughts about this elephant can depend on one act of attention.

When this happens, trading on identity is legitimate.

Sense is that, sameness of which makes trading on identity legitimate.

When two thoughts about this elephant depend on one act of attention, they involve a single sense.

?

same act of attention -> same sense

When two utterances of a word (or phrase) are controlled by a single act of attention, they have the same sense.

‘the notion of conscious attention to an object has an explanatory role to play: it has to explain how it is that we have knowledge of the reference of a demonstrative.

‘This means that conscious attention to an object must be thought of as more primitive than thought about the object.

‘It is a state more primitive than thought about an object, to which we can appeal in explaining how it is that we can think about the thing’

Campbell, 2002 p. 45

‘We might argue that the mode of presentation of a perceptually demonstrated object has to be characterized

... in terms of the property that the subject uses to select that object perceptually.

Sameness of mode of presentation is the same thing as sameness of the property on the basis of which the object is selected;

difference of mode of presentation is the same thing as difference of the property on the basis of which the object is selected.’

Campbell, 2011 p. 341

?

same act of attention -> same sense

When two utterances of a word (or phrase) are controlled by a single act of attention, they have the same sense.

✗

What is sense supposed to do?

1. Sense explains the difference in informativeness between the utterance of ‘Charly is Charly’ and ‘Charly is Samantha’.

2. Sense determines reference.

3. A statement showing the sense of a name specifies what you need to know about the utterance of a name in order to understand it.

?

same act of attention -> same sense

When two utterances of a word (or phrase) are controlled by a single act of attention, they have the same sense.

The sense of an utterance of a word (or phrase)

is what you know when you

have knowledge of reference.

✗

ftbe:

Communicators can know, sometimes,

whether they are understanding.

How?

Utterers make rational, voluntary use of some regularites

while merely conforming to others.

How is this possible?

∴ there is a mental state of the utterer in virtue of which her utterance refers to ‘Earth’.

Call this mental state ‘knowledge of reference’.

same act of attention -> same sense

within a person ✓

between people (an utter and her audience) ✗

Contrast descriptions: understanding you means associating the same description with the word.

Conscious attention isn’t enough for understanding because ‘it can happen that I am consciously attending to the building to which you are referring, even though I do not realize that it is the building to which you are referring. Conscious attention to the building is not in itself an understanding of your remark: I have to make a link between that conscious attention and the demonstrative you use [see chapters 1-2 and 6-7]’

Campbell, 2002 p. 5

?

same act of attention -> same sense

When two utterances of a word (or phrase) are controlled by a single act of attention, they have the same sense.

**** TODO Summary

NEXT : ensuring matching acts of attention (why might you point, or move next to someone when using a perceptual demonstrative?)

The Picture

What are the facts to be explained?

1. This utterance of ‘Ayesha smells’ depends for its truth on how Ayesha is, unlike that utterance of ‘Beatrice smells’. Why?

2. This utterance of ‘Charly is Charly’ was less revelatory than that utterance of ‘Charly is Samantha’. Why?

3. Humans successfully achieve ends by uttering words. How?

4. Communicators can know, sometimes, whether they are understanding. How?

5. Utterers make rational, voluntary use of some regularites while merely conforming to others. How is this possible?

The Picture

#1 ∴ there is a word-thing relation; call it ‘reference’.

Reference, if it exists, must explain #1 and #3.

#2 ∴ meaning isn’t only reference; call the aspect which explains #2 ‘sense’.

Knowledge of reference, if it exists must explain #4 and #5.

The sense of an utterance is what you know when you have knowledge of reference.

Sometimes the sense of an utterance is a description.

But not always.

Sometimes the sense of an utterance is individuated by an act of attention.

conclusion: some senses are descriptions, others are modes of acquaintance.

Massive Reduplication

If your utterance of a word refers to a thing, then ...

1. you must be acquainted with that thing;

2. you must either be acquainted with it or else know it by description; or

3. you need neither acquintace nor knowledge by description.

Russell’s idea:

Reference requires acquaintance knowledge of reference

Objection: in uttering ‘Julius Caesar drank the Rubicon’, I refered to Julius despite not being acquainted with him.

Reply: ‘Julius Caesar’ is actually a quantifier phrase (specifically, a description), so I did not refer.

Objection: rigid designators (Kripke)

Reply: descriptions can be rigidified

Objection: ...

...

For all we know, a distant region of the universe may contain qualitatively indistinguisable duplicates of everything here.

Therefore: For all we know, even our most elaborate descriptions may fail to pick out individuals.

Therefore: When we rely on descriptions, we may fail to single out a unique object for all we know.

Therefore: If we relied only on descriptions, we may, for all we know, never single out a unique object.

But: We know that our utterances sometimes succeed in singling out a unique object.

Knowledge of Reference and Pragmatics

Reference

Steve’s 13:11 utterance of ‘Earth’ refers to Earth

Knowledge of Reference : what is meant?

1. Steve knows Earth (either by acquiantance or description).

2. Steve knows that his 13:11 utterance of ‘Earth’ refers to Earth.

3. There is a state of Steve’s mind in virtue of which his 13:11 utterance of ‘Earth’ refers to Earth.

Q1 What, if anything, is that state of mind?

Q2 Why think there any such thing as this state of mind?

At bottom, communication with words is a matter of following rules.

This can be done without any insight into why the rules are as they are.

Therefore mental states of communicators in virtue of which their utterances refer are unnecessary for characterising reference.

cf Putnam 1978

‘I’ve had a great evening. This wasn’t it.’

MS, the meaning of the sentence;

PE, the proposition expressed; and

PM, the proposition meant.

Neale, 1990 p. 75

I have had breakfast.

I have had a kidney removed.

I have had fermented fish for breakfast.

I have had a great evening.

Among utterances of these sentences,

there can be is variation in the PM

although Compositionality does not permit corresponding variation in MS.

Given that MS is a function from contexts of utterance to propositions,

the values of this function will not typically be a PM.

Terminology: Call the value of MS in a given context of utterance the ‘proposition expressed (PE)’.

MS, the meaning of the sentence;

PE, the proposition expressed; and

PM, the proposition meant.

Neale, 1990 p. 75

How do you get from PE to PM?

reasoning about cooperation (Grice)

searching for relevance (Sperber & Wilson)

At bottom, communication with words is a matter of following rules.

This can be done without any insight into why the rules are as they are.

Therefore mental states of communicators in virtue of which their utterances refer are unnecessary for characterising reference.

cf Putnam 1978

Two Arguments

1. Communication with words involves successful communication of a PM.

2. Which PMs an utterance communicates depends on context in arbitrarily complex, uncodifiable ways.

Therefore,

3. communication with words cannot be entirely a mechanical, script-following, rule-bound

activity.

1. Arriving at a PM depends on taking the PE and searching for cooperation or relevance.

Therefore,

2. communication requires representing PEs, which requires knowledge of reference.

Reference

Steve’s 13:11 utterance of ‘Earth’ refers to Earth

Knowledge of Reference : what is meant?

1. Steve knows Earth (either by acquiantance or description).

3. There is a state of Steve’s mind in virtue of which his 13:11 utterance of ‘Earth’ refers to Earth.

Q1 What, if anything, is that state of mind?

Q2 Why think there any such thing as this state of mind?

When the utterance of a word refers to a thing,

must the utterer have knowledge of reference?

What is the relation between

an utterance of a word (or phrase)

and a thing

when the utterance refers to the thing?

It is a psychological relation.