Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

What is the meaning of ‘Earth’?

Simple idea: ‘Earth’ means Earth.

The meaning of an utterance of a word is the thing it refers to.

Is there anything meanings are needed to explain which we cannot explain if we take this view of them?

‘entities such as meanings ...

are not of independent interest’

Davidson, 1974 p. 154

What is the meaning of ‘Earth’?

Simple idea: ‘Earth’ means Earth.

The meaning of an utterance of a word is the thing it refers to.

Is there anything meanings are needed to explain which we cannot explain if we take this view of them?

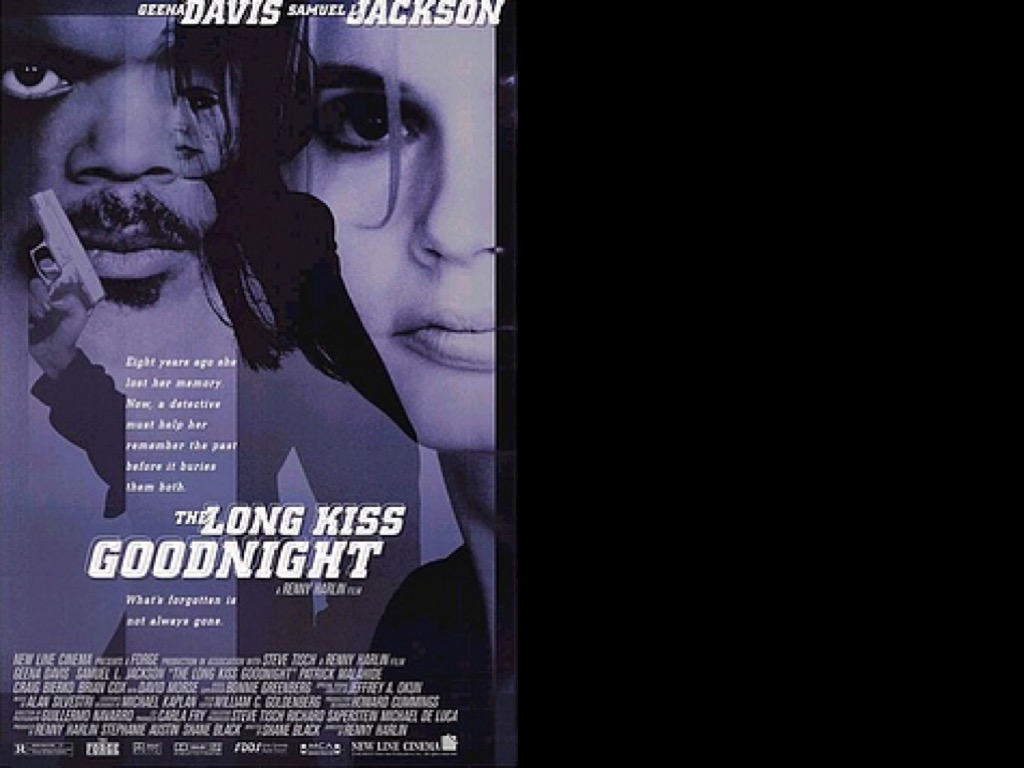

Samantha Caine

Suburban homemaker and the ideal mom to her 8 year old daughter Caitlin. She lives in a New England small town, teaches in a local school and makes the best Rice Krispie treats in town.

Charly Baltimore

a highly trained secret agent and cold-blooded killer involved in the government's most unscrupulous affairs.

Charly is Charly.

Charly is Samantha.

‘What is stated in the proposition ‘Charly is Samantha’ is certainly not the same thing as the content of the proposition ‘Charly is Charly’.

Now if what corresponded to the name ‘Samantha’ as part of the thought was the reference of the name and hence the woman herself, then this would be the same in both thoughts.

The thought expressed in ‘Charly is Samantha’ would have to coincide with the one in ‘Charly is Charly’, which is far from being the case’

Frege, 1892[1993] p. 44

Charly Baltimore lives in New England

Samantha Caine lives in New England

‘Someone who takes the latter to be true need not … take the former to be true

‘An object can be determined in different ways, and every one of these ways of determining it can give rise to a special name, and these different names have different senses’

Frege, 1892[1993] p. 44

What is the meaning of ‘Earth’?

Simple idea: ‘Earth’ means Earth.

The meaning of an utterance of a word is the thing it refers to.

Is there anything meanings are needed to explain which we cannot explain if we take this view of them?

Contrast an utterance of ‘Charly is Charly’ with an utterance ‘Charly is Samantha’

ftbe: These may differ in informativeness.

idea: This difference is due to some difference in the meanings of the utterances of ‘Charly’ and of ‘Samantha’.

There could be no such difference if the meaning of an utterance of a word were merely the thing it refers to.

Conclusion: the meaning of an utterance of a word is not, or not only, the thing it refers to.

What are senses?

‘Frege’s idea was that to understand an expression, one must not merely think of the reference that it is the reference, but that one must, in so thinking, think of the reference in a particular way.

The way in which one must think of the reference of an expression in order to understand it is that expression’s sense’

Evans, 1981 [1985]: 294

Summary so far

1. Can the meaning of an utterance of a word be the thing it refers to?

2. Sense is that aspect of meaning, if any, which explains patterns of difference in informativeness despite sameness of reference.

3. Rougly, senses are ‘the way in which one must think of the reference of an [utterance of] an expression in order to understand it’.

Preview

What is sense supposed to do?

1. Sense explains the difference in informativeness between the utterance of ‘Charly is Charly’ and ‘Charly is Samantha’.

2. Sense determines reference.

3. A statement showing the sense of a name specifies what you need to know about the utterance of a name in order to understand it.

The sense of an utterance of ‘Charly Baltimore’ is this description:

the highly trained secret agent suffering from amnesia in New England.

The sense of an utterance of ‘Samantha Caine’ is this description:

the New England teacher with an 8 year old daughter who makes the best Rice Krispie treats in town.

Are senses descriptions?

Forget about sense for now.

I utter ‘Ayesha smells’ and, then, ‘Beatrice smells’.

Observation: My first utterance is true because of how Ayesha is, my second because of how Beatrice is.

Question: Why do they differ in this way?

Rough idea: because my utterance of ‘Ayesha‘ stands in some relation to Ayesha.

Terminology: call this relation ‘reference’.

What, if anything, is reference?

Russell’s idea:

Reference requires acquaintance

Russell’s Argument on Acquaintance

‘Every proposition which we can understand must be composed wholly of constituents with which we are acquainted’

\citep[p.~209]{Russell:1910fa}

Russell, 1910 [1963] p. 209

What is Russell’s argument?

‘Whenever a relation of supposing or judging occurs, the terms to which the supposing or judging mind is related by the relation of supposing or judging //p. 211// must be terms with which the mind in question is acquainted. This is merely to say that

we cannot make a judgement or a supposition without knowing what it is that we are making our judgement or supposition about.

It seems to me that the truth of this principle is evident as soon as the principle is understood’

Russell, 2010 pp. 210-11

‘I think the theory that judgements consist of ideas ... is fundamentally mistaken.

The view seems to be that there is some mental existent which may be called the ‘idea’ of something outside the mind of the person who has the idea, and that, since judgement is a mental event, its constituents must be constituents of the mind of the person judging.

But in this view ideas become a veil between us and outside things—we never really, in knowledge, attain //p. 212// to the things we are supposed to be knowing about, but only to the ideas of those things.

The relation of mind, idea, and object, on this view, is utterly obscure ...

I ... see no reason to believe that, when we are acquainted with an object, there is in us something which can be called the ‘idea’ of the object.

On the contrary, I hold that acquaintance is wholly a relation, not demanding any such constituent of the mind as is supposed by advocates of ‘ideas’.’

Russell, 1910 [1963] pp. 211–2

Reconstruction of Russell’s argument

Judgements are about objects in the world. [intentionality]

Any theory of judgement needs to elucidate the relation between a judgement and an object.

Invoking ideas to do this makes intentionality more, not less, obscure.

Therefore:

The intentionality of judgement consists at bottom in a relation between a thinker and an object.

Terminology: call this relation ‘acquaintance’.

How to get from

the relation between a judgement and an object

to

the relation between a word and an object?

The utterance of a sentence expresses a judgement.

The audience’s task is to infer the judgement from the words.

They can do this because the words uttered correspond to parts of the judgement.

Reconstruction of Russell’s argument

Judgements are about objects in the world. [intentionality]

Any theory of judgement needs to elucidate the relation between a judgement and an object.

Invoking ideas to do this makes intentionality more, not less, obscure.

Therefore:

The intentionality of judgement consists at bottom in a relation between a thinker and an object.

Terminology: call this relation ‘acquaintance’.

Possible project: Evaluate Russell’s case for the Principle of Acquintance.

Summary

Russell’s idea:

Reference requires acquaintance.

Russell’s argument:

Objects are constituents of judgements because ideas obscure the relation between judgements and objects ...

The Standard Route

Russell’s idea:

Reference requires acquaintance knowledge of reference

Objection: in uttering ‘Julius Caesar drank the Rubicon’, I refered to Julius despite not being acquainted with him.

Reply: ‘Julius Caesar’ is actually a quantifier phrase (specifically, a description), so I did not refer.

Objection: rigid designators (Kripke)

Reply: descriptions can be rigidified

Objection: ...

...

‘we have acquaintance with anything of which we are directly aware, without the intermediary of any process of inference or any knowledge of truths’

\citep[chapter 5]{Russell:1912ln}

Russell, 1912 chapter 5

‘We have descriptive knowledge of an object when we know that it is the object having some property or properties with which we are acquainted; that is to say, when we know that the property or properties in question belong to one object and no more, we are said to have knowledge of that one object by description, whether or not we are acquainted with the object.’

\citep[p.~220]{Russell:1910fa}

Russell, 1910 p. 220

Does reference require knowledge of the referent?

My proposal:

1. There are multiple, internally consistent characterisations of reference.

2. If our aim were only to explain The Difference, there would be no ground for preferring one over all others.

Knowledge of Reference (Part 1)

Reference

Steve’s 13:11 utterance of ‘Earth’ refers to Earth

Knowledge of Reference

The state of Steve’s mind in virtue of which his 13:11 utterance of ‘Earth’ refers to Earth

What, if anything, is that state of mind?

Maybe: Knowledge of reference is acquaintance?

I.e. you have knowledge of reference concerning the utterance of a word when you are acquainted with its referent.

Objection: you might be acquainted with the referent while unaware of any connection between it and the utterance.

Why think there any such thing as knowledge of reference?

‘A number of tools have this feature: that the instructions for use of the tool do not mention something that explains the successful use of the tool.

For example, the instructions for turning an electric light on and off – ‘just flip the switch’ – do not mention electricity.

But the explanation of the success of switch-flipping as a method for getting lights to go on and off certainly does mention electricity.

It is in this sense that reference and truth have less to do with understanding language than philosophers have tended to assume’

Putnam, 1978 p. 99

New fact to be explained:

Humans successfully achieve ends by uttering words.

Guess: An explanation of how this is possible will hinge on a particular way of relating utterances of words to things.

Terminology: This relation is reference.

Old fact to be explained:

By changing the words uttered you can change which things an utterance depends on for its truth.

Guess: an explanation of why this occurs will hinge on a particular way of relating utterances of words to things.

Substantive claim: This relation is reference (i.e. the same as that one <--).

When the utterance of a word refers to a thing, must the utterer have knowledge of reference?

Putnam: no.

‘There is a common-sense picture of the relation between knowledge of reference and pattern of use.

... you use the word the way you do because you know what it stands for’

Campbell, 2002 p. 4

Example : misspeaking

I utter ‘Elliot is a spy’.

But I misspoke.

I might clarify, ‘I meant to say that Philby, not Elliot, is a spy’.

Why does my utterance count as misspeaking?

Candidate explanation: Because my acquaintance with Philby was causing my use of the word ‘Elliot’.

‘There is a common-sense picture of the relation between knowledge of reference and pattern of use.

... you use the word the way you do because you know what it stands for’

Campbell, 2002 p. 4